A country divided: Helicopter travel and homelessness in Brazil

Poor people have been forced from their homes. Rich people have been forced to reduce their helicopter trips.

The recession has hit all of Brazil – and contributed to the election of a dictatorship-friendly president in Latin America’s largest democracy.

São Paulo is the helicopter capital of the world.

“Ready for departure,” says the pilot and grabs the levers.

The helicopter shakes as it takes off. The landing pad on the roof of the Maksoud Plaza Hotel shrinks before it disappears from sight.

Once in the air, the vastness of São Paulo becomes evident. An apparently endless forest of skyscrapers reaches for the sky. Latin America’s financial centre and largest city is home to 24 million people. It is also the helicopter capital of the world.

By car, a trip from the posh business boulevard Avenida Paulista to the upper-class suburb of Alphaville takes at least two hours. By helicopter, it’s only nine minutes.

“Imagine soaring over rush-hour traffic on your way to work. This would be a dream come true for anyone who has endured a commute in any of the world’s largest cities,” writes Voom on its site.

The company, owned by the French giant Airbus, has launched itself as an airborne counterpart to Uber. Ride-sharing will push prices down and “democratise” helicopter travel.

“It’s mostly the upper middle class that travels with us,” says the pilot after landing among the greenery and gated communities of Alphaville.

By contrats, the richest have their own helicopters, or charter private flights from one of the city’s many helicopter taxi companies. But they don’t want to discuss their travel habits.

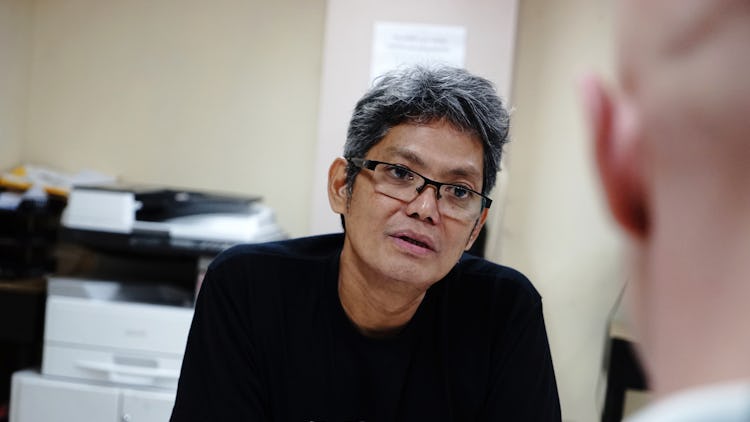

“Unfortunately, it’s impossible,” says Rafael Dylis, chief business officer at Helimarte Taxi Aereo, when asked about setting up an interview with is clients.

“They are not interested in attention.”

Rafael Dylis, chief of executive flights at Helimarte. Photo: CH Gardiner

That trip takes hours by car and they are willing to pay to avoid it.

Several things have contributed to São Paulo’s position as the global hotspot of helicopter travel.

Its massive size, an under-dimensioned public transport system, a car-dependent middle class that creates congestion, high land prices that have resulted in tall buildings suitable for helicopter landing pads.

And of course, a critical mass of people with deep-enough pockets.

“We have business districts in the south while the powerful people live in the north. That trip takes hours by car and they are willing to pay to avoid it,” says Rafael Dylis.

Money is the prerequisite. But the sales argument is time – time to live, time to spend with the kids, time that doesn’t need to be spent in the endless car queues 500 metres below. But in recent years, fewer people have been able to pay for that time.

“It’s a luxury service and in 2014, the number of executive flights dropped dramatically due to the economic crisis. We had more pilots before but had to scale down. Then, we had 14 helicopters. Now, there are nine left,” says Rafael Dylis.

After decades of growth, the Brazilian economy came to a halt in mid-2014.

The reasons were several and interdependent. Falling commodity prices, fewer orders from China, reduced foreign investment in the wake of the international financial crisis, corruption and inefficient government administration.

The subsequent recession was the worst in a century. Unemployment doubled. The budget deficit reached record levels. The roaring of the rotor blades died down.

“Today, there are very few flights. It’s the same for everyone. Even when we count flights to our customers’ beach houses, it has decreased,” says Rafael Dylis.

Taxi operations that used to make up the majority of revenue now accounts for only 30 per cent. The company has been forced to diversify to survive.

“We bring a technician on the flights to inspect power lines, and we also monitor the Venezuelan border to investigate where refugees try to cross.”

Bolsonaro supporters celebrating on election night. Photo: CH Gardiner

I paid rent and supported four daughters. And then interest rates went up.

The recession hit the entire community, but the least resistant people took the brunt of the blow.

When the crisis came, Juliana Silva Antonachi lived in Guaianases on the outer edge of São Paulo. The income from working as a street vendors fell as fast as expenses rose.

“I paid rent and supported four daughters. And then interest rates went up.”

Juliana Silva Antonachi and her husband managed to find a cheaper accommodation. But in the end – despite counting every centavo – it was not enough.

“What was really difficult was the electricity and water bills,” she says.

Today, Juliana Silva Antonachi considers herself fortunate. When the recession forced low-income earners from their homes, she unexpectedly found an alternative.

“I met an old neighbour who was part of the movement, and she said I should come and live with them. I was shocked and said I was not a squatter. But she said ‘come by and see how it is’. So I came here, and I have stayed here ever since.”

Juliana Silva Antonachi never considered herself a ”squatter”. Now she doesn’t want to leave. Photo: CH Gardiner

I would stay here even if the economy improved.

When MMLJ – the Movement for residents fighting for justice – took over the old hotel in the Luz district, it had been neglected and abandoned for many years. Today, the building is home to 237 families and is known as Ocupa Mauá.

The membership rules are extensive. An introduction to the values and strategies of the movement is mandatory before moving in. Residents must participate in cleaning days and meetings about common issues. Alcohol and drugs are not allowed and there is zero tolerance for domestic violence.

The neighbourhood is poor and crime-riddled – Ocupa Mauá is a stone’s throw from lawless Cracolândia – but Juliana Silva Antonachi has never felt so safe.

“I can leave my daughters here and no one will mess with them. We trust each other here.

But Ocupa Mauá offers more than security. The organisation is an antidote to poverty. The costs of electricity, water and purchases are shared equally. The cost of living is a third of market costs. Suddenly, there is enough money to support the family. Including its latest addition – a fifth daughter – who arrived two months ago.

“I would stay here even if the economy improved. Apart from your average misunderstandings between neighbours, everyone here is very united,” says Juliana Silva Antonachi.

But politically, there are clouds on the horizon. Brazil’s newly-elected president Jair Bolsonaro has said that property owners should be allowed to shoot squatters.

“It upset me that he was elected,” Juliana Silva Antonachi says. “I think that us poor people in Brazil will suffer a lot.”

Ocupa Mauá, an abandoned hotel that now houses 237 families. Photo: CH Gardiner

Random calls for violence were common during Bolsonaro’s campaign.

He talked about physically disciplining children who showed signs of homosexuality, mowing down Workers’ Party supporters with machine guns, and rewarding police officers shooting to kill with medals.

Bolsonaro fans generally dismiss these statements, but there is a genuine concern among the groups that the threats are aimed at. What if the president is serious? Or if his supporters take him by his words?

How could Latin America’s largest democracy elect Bolsonaro, a candidate on the far right, who has defended torture and praised dictatorships?

“I don’t think he’s really like that. There’s been a lot of fake news, a lot of false information,” says Sergio Santos.

He is the CEO of a manufacturing company with about 20 employees, and heads the local Chamber of Commerce in Cordeirópolis a few miles outside São Paulo. He is also part of the social layer that determined the election at the polls.

The Workers’ Party has a solid support among poor Brazilians. Jair Bolsonaro was able to challenge by gaining the support of evangelical churches, nationalists, the economic elite and protest voters.

But in the most polarised election since the military dictatorship was abolished in 1985, the votes in the political centre determined the outcome in the second round.

Sergio Santos, CEO. Photo: CH Gardiner

I think Bolsonaro will be good for business.

Bolsonaro was not Segio Santo’s first choice. Voting for the far right candidate was, he says, a way to stop socialism.

“The Workers’ Party brought the country down. They didn’t think of the people. If they had won, Brazil would have followed the road that Venezuela and other countries had taken towards dictatorship.”

Ultimately, Sergio Santos says the election was about the economy.

“I think Bolsonaro will be good for business. In the Chamber of Commerce, everyone wanted change. The industry has suffered for several years now. And if the Workers’ Party had won, they’d have raised taxes on the first day and investments would have gone down.”

The issues of corruption, crime and punishment and traditional values featured heavily in the election campaign and favoured Bolsonaro.

But the economy was the only issue prioritised by all groups of voters. The poor who remember welfare initiatives under president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva voted for increased redistribution. Sergio Santos and his friends in the Chamber of Commerce voted against.

During the noughties, almost 30 million Brazilians were lifted from poverty. But the gaps between the country’s rich and poor remained deep, and began to grow again during the recession.

The Brazil’s six richest individuals own as much as the poorest 100 million. The 5 wealthiest per cent earn as much as the remaining 95.

Teresa de Jesus Neves has turned 70, and has spent the most of her years selling jewellery and handmade bracelets in central São Paulo.

“I’m on a pension, but that’s only enough for the hairdresser and my nails,” she laughs.

Like everyone else, she says that the last few years have been tough.

“It has been very difficult. I manage to survive but it’s a lot of work. I’m here 13-14 hours every day. Then I come home and continue to work.”

She voted for the Workers’ Party. Her dream is taking a step away from the informal work sector.

“What really would help me is if they legalised my job.”

Teresa de Jesus Neves ekes out a living selling jewelry on the street. Photo: CH Gardiner

I’m on a pension, but that’s only enough for the hairdresser and my nails.

Three years ago, she was given a temporary license to conduct sales on the city’s busiest street. At home, seven children and eight grandchildren struggle to make the household go around, so the number of passers-by makes a difference to the day’s takings.

Teresa de Jesus Neves says she would stay all night if her daughters wouldn’t drag her home.

On her table, the silver details of her jewellery glow in the shine from a single low-energy lamp. All around, Avenida Paulista’s skyscrapers stand tall.

A striking number have helipads on their roofs.

BACKGROUND

Lula

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Brazil’s president from 2003-2011, aimed for a comeback in the presidential election but was detained for corruption in April. At the time, he had twice thesupport of Bolsonaro, but in September he was denied the right to run for office, and the Workers’ Party’s vice-candidate Fernando Haddad was forced to step forward.

The Workers’ Party calls the process against Lula politically motivated. An accusation that hardly was put to rest when Sérgio Moro, the prosecutor who ran the case against Lula, was recently appointed Minister of Justice in Jair Bolsonaro’s government.

Operation car wash

The biggest known corruption saga in the world history began to emerge in 2014 and so far hundreds of politicians and business executives have been prosecuted and convicted.

The investigation has been called a political attack against the Labor Party, but influential right-wing politicians have also been indicted.

Despite the fact that politicians of all persuasions have been implicated, Operation Car Wash has largely been linked with the Workers’ Party, which already had a tainted reputation since a 2004 corruption scandal.

Bolsonaro

Ex-military man Jair Bolsonaro has been a congressional representative of Rio de Janeiro since 1991 and has during that time swapped parties on several occasions.

He ran on a platform of social conservatism, economic liberalism and a hard stance on crime. When corruption became one of the biggest election issues, Bolsonaro benefited from being able to promote himself as clean.

Brazil

Brazil has almost 210 million citizens. Latin America’s most populous state is the world’s fourth largest democracy and tenth largest economy.

In 2003, 24.9 percent of the population lived below the national poverty line, according to the World Bank. In 2014, after massive welfare initiatives implemented by the Workers’ Party, that proportion had fallen to 7.4 percent. 2015, one year after the recession began, this had risen to 8.7 percent.

Brazil was ruled by a military junta from 1964-1985. A number of industrial strikes, led by a young metal worker named Lula, weakened the dictatorship and contributed to its final downfall.