The dream of a better life

Found throughout Europe, many Romani have left Romania in the hope of a better life. Arbetet Global’s Erik Larsson travelled to a Romani village in Romania and found extreme poverty side by side with enormous villas surrounded by gold-coloured fences.

Ghiulbie Saban sits on a blanket wrapped over a red plastic crate on the footpath at Odenplan in Stockholm, Sweden.

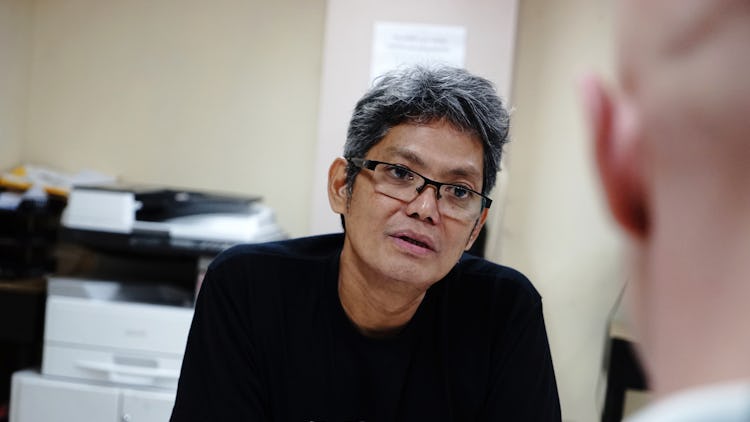

ROMANIA. Sitting in his large office, where a Romanian flag hangs on the wall behind the desk, Georgian Caraman has spent nearly 45 minutes explaining that the “gypsies” drive expensive BMW and Mercedes cars and live in flashy homes.

He is mayor of the small town of Babadag, home to 10,000 people, 3,000 of which are Romani.

Many of the town’s Romani residents go to Sweden – or Portugal – to support themselves.

Georgian Caraman first says that everyone that goes to Sweden to beg for money is actually well off.

“Everyone?”

“Everyone,” he replies.

Later, he hurries down the stairs of the town hall and orders a policeman to “show the houses, show the expensive cars”.

The policeman nods.

“Jump in,” he says, and starts the police car.

***

In another part of town, Ghiulbie Saban sits on a concrete block in the yard outside her dilapidated house.

Ghiulbie Saban is 29 years old and has two children – a 7-year-old daughter and an 11-year-old son. She has just returned to Romania from Sweden.

“I usually sit and beg at Odenplan,” she says in broken Swedish.

Since 2014, she has travelled back and forth between Babadag and Stockholm, Sweden. The money she has earned from begging has paid for the run-down house.

“I want my children to have a better life than mine. To have a real home,” she says, adding that she bought the house for the equivalent of 70,000 SEK (7000 euros).

“But we could only afford to pay half. The seller is a good person and lets me pay the rest when I’ve got some more money.”

Ghiulbie Sabans house in Babadag. Photo: Alexandru Socol

Some young men and women with children appear on the property. Ghiulbie Saban introduces one of them as her younger sister, and the men as cousins who will help renovate the house.

They say hello, cautiously at first.

Smoking their cigarettes in silence. After half an hour, the father – Regei Ismael Buha – takes my arm and pulls me towards the house. He shows the mess inside and says that four of his five children went to Sweden to beg.

We resume our conversation about work when we get back outside.

“I’d rather work than beg,” Ghiulbie Saban interjects.

“So why don’t you?” I ask.

***

Romania’s labour market is red hot.

The unemployment rate of 4.6 per cent is lower than EU average – 7.1 per cent and wages have risen sharply in the past year. Still, 20 per cent of all working-age residents have travelled abroad to work, mostly throughout the EU.

Sociologist Gelu Duminica, at the University of Bucharest, says that the reason that so many travel abroad is simple.

“It’s the same old story; for the past 4,000 years, people all over the world have moved because they want a better life.”

But the question remains; why won’t Ghiulbie Saban and others take the vacant jobs available in Romania?

According to the World Bank and other sources, there is a big problem with job matching. Companies in Bucharest and other growth areas can’t find workers while unemployment is high in rural areas. Many cannot move to areas where jobs are available.

Those who sell their rural homes don’t get enough money to buy one where work is available. Bad road networks also makes commuting for work difficult.

”But I don’t get any jobs!” Ghiulbie Saban responds to my question.

***

We travel past several newly built houses with gold and silver-coloured fences. The policeman drives up and down the streets.

“And there we have a Romani family,” the policeman says every now and then.

The houses are several storeys high and a strikingly large portion of them are newly built. Several of the well-polished fences are adorned by the emblem of Italian fashion house Versace – a sign of luxury and wealth.

But then the policeman says something else.

“You see a house like that,” he says when the car stops. “Many people can live in it. 30 people, sometimes more.”

He adds that the houses may look luxurious from a distance, but in some cases the materials are cheap and indoors, the interior can be very basic.

Several people I talk to say the same thing. The luxury is mainly on the surface.

Newly built house in Babadag. Photo: Alexandru Socol

***

People rush past in the scorching sunshine. Ghiulbie Saban sits on a blanket wrapped over a red plastic crate on the footpath at Odenplan in Stockholm, Sweden.

It’s half past four in the afternoon and she says it’s not been a great day.

“I’ve got 70 crowns (7 euro)” she says, holding up a paper mug with a few coins in it.

She has been sitting on the street corner since seven o’clock in the morning and will stay until seven in the evening.

It used to be easier. In 2014, when she began to beg in Sweden, she could get 200-300 crowns a day (20-30 euros). These days, she gets about 150 crowns.

The next time we meet, a day later, the weather is worse and it’s been raining overnight.

“It’s okay though. I didn’t get wet. My shelter has a roof. But the cars are a problem. I hear motor noise all night and have trouble sleeping.”

She is tired and says she wants to go home. Her 7-year-old daughter left behind in Romania wasn’t feeling well during the night and school holidays start soon.

At the same time, she needs the money. She says the roof of her house has now been fixed but she’s out of money for the renovation. She needs to buy a front door, flooring and plaster for the walls.

Ghiulbie Saban doesn’t have time to talk anymore.

It’s almost 12 o’clock and she’s about to meet a friend.

They will clean the home of a Swedish family. She expects to be paid for two or three hours today; money that she can use to renovate her house.

“It’s a lot better than just sitting here,” she says, starting to pick up her stuff from the street.

This article was first published in swedish. Translation: Liselotte Geary

Capital: Bucharest

Population: 21.5 million

Unemployment rate: 4.6 percent (EU average is 7.1 percent, in Sweden it is 6.2 percent)

Economy: One of the EU’s fastest-growing, the Romanian economy is forecast to grow by 4.5 per cent this year. Wages are also rising sharply, 13 per cent in the past year. But the growth is from a low baseline, and dissatisfaction with the country’s political system – plagued by corruption scandals – is high. Despite wage increases, the risk of poverty is the highest in the EU, along with Bulgaria. Nearly 20 percent of the population between 20 and 64 years old are working or living in another EU country, which is far more than in all other EU countries.

The Romani

The Romani are Europe´s largest ethnic minority and live around the world.

By studying Romani Chib – the Romani language – researchers have found that the Romani’s ancestors lived in India until the 700s and 1100s before starting to migrate westwards. In the 13th century, the Romani came to Europe, and from the 14th century the Romani were enslaved, in Romania for example. Slavery in Romania ceased as late as 1856. Many Romani were then forced to roam for survival.

The Romani have been persecuted for hundreds of years and the Nazis arrested the Romani under the pretence that it was a matter of crime prevention.

Because the Romani are spread all over the world, their culture and religion vary greatly. There are both Christian and Muslim Romani. In Babadag, where Arbetet Global visited, most Romani are Muslim and have close ties to Turkey.

Source: Our Romani history