Independent trade unions ’fighting for survival’ in Algeria

After an Algerian minister singled out union leader Raouf Mellal for “hounding” the government, repression against him intensified. Now Mellal has been forced into exile, while the independent unions in Algeria are fighting for their survival.

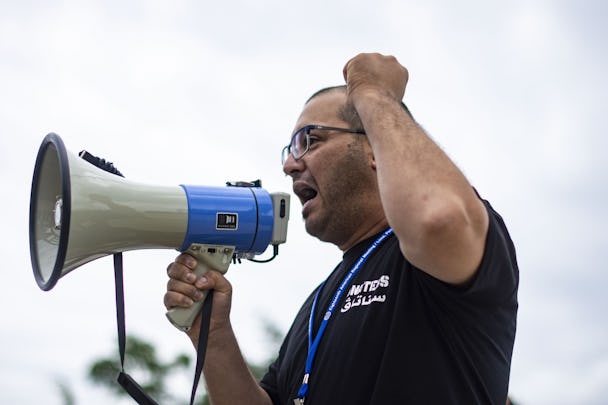

After multiple arrests and having been branded a foreign agent, Raouf Mellal (center) decided to flee Algeria.

In 2018, the Algerian minister for Labour, Mourad Zemali, singled out two independent trade unions for “hounding” the government.

Along with Rachid Maalaoui, of public sector union Snapap, Raouf Mellal of the energy workers union Snateg was accused of trying to defame Algeria by reporting labour rights violations to the ILO.

“For having filed complaints with the ILO, I was sued for defamation by the Labour Minister. I was sentenced to six months in prison, but the sentencing was done in absentia. I woke up one morning to find out that I had been sentenced”, says Roauf Mellal through an interpreter.

Prosecution of union leaders

It wasn’t the first time Roauf Mellal had experienced repression. The year before he had been fired, along with 1,200 union members, after organizing a strike at state owned electricity company Sonelgaz.

“The government’s response was twofold,” he says. “On one hand it moved to do a fraudulent administrative dissolution of the union. On the other hand 14 union leaders, including myself, were prosecuted.”

With the ministers statement, the harassment from authorities increased further.

As it turned out, that was only the beginning.

Unions supporting democracy

In 2019, millions of Algerians took to the streets during the peaceful democracy protests known as the Hirak, or the Revolution of Smiles. The immediate aim was to prevent long term President Abdelaziz Bouteflika from seeking a fifth term in office. But the movement also wanted to transform Algerian society.

“The independent unions gave the Hirak total support. We too wanted to bring about democratic change in Algeria. The specific contribution of the unions was to organize a series of mass strikes which played a significant role in putting an end to Bouteflika’s plans”, says Raouf Mellal.

Faced with massive public discontent, Algerias military quickly forced Bouteflika to step down. In an election where all of the candidates had close ties to the previous administration, former Prime Minister Abdelmadjid Tebboune was finally elected President.

“It didn’t signify any change in power relations in the country,” says Raouf Mellal. “They had to ditch Bouteflika, but basically the military’s grip on the country was not disturbed.”

There were endless lawsuits, endless fines. I lost count, I think there where maybe twenty lawsuits against me

Algeria targeting independent unions

When the calls for democracy didn’t subside, the military targeted independent unions and human rights defenders.

“There were endless lawsuits, endless fines. I lost count, I think there where maybe twenty lawsuits against me. Everyday the police would come to my home to serve some new accusation”, recalls Raouf Mellal.

In April 2019, he was violently arrested.

“He put his knee on my neck, and in detention I was abused and treated in a very humiliating way. It didn’t break my spirit, but the damage to my body will last. I suffer from back pains now. After that, I realized I was no longer physically safe in Algeria.”

In the end, Raouf Mellal was left with no choice. Two years ago, he left Algeria.

“The accusations against me kept getting more and more serious, culminating in me being accused of being a foreign agent. I risked the death penalty or life in prison and decided to flee.”

The pandemic used to criminalize dissent

The Hirak, however, continued. At least until the pandemic gave the Algerian regime a convenient excuse.

“Covid-19 took the movement of the streets, people were obliged to stay home. And it was at that movement that the mass repression came. They used the pandemic to criminalize dissent,” says Raouf Mellal.

Several new laws have been adopted, targeting the protest movement.

“The situation with has gotten much worse, particularly since last year with when the penal code was amended to include a new, very loose, definition of terrorism. That law has allowed for a dozen trade unionists to be prosecuted for terrorism,” says Raouf Mellal.

Political prisoners on hunger strike

In the wake of the new terrorism law followed a wave of arbitrary detentions. Since the end of January, some 40 political prisoners are on hunger strike in Algerian prisons. A friend of Raouf Mellal, from the trade union of informal workers, has been imprisoned for eight months without a date being set for his trial. He is facing terrorism charges.

“There were arrests before as well, but you knew that in a month or two you would be sentenced. You knew what the alleged crime was and what the punishment would be. Now you know nothing,” says Raouf Mellal. “The atmosphere of fear is unimaginable.”

No more than a few years ago, Algeria’s independent trade unions were strong enough to face-off with the regime. Now they are barely clinging to existence.

“All public activity is impossible at the moment,” says Raouf Mellal. “We are in a fight for our survival.”

Deterioration of human rights

The European Parliament has adopted resolutions condemning the deterioration of human rights in Algeria, explicitly mentioning the attacks on trade unionist. But the harsh words has not been translated into foreign policy, and Algeria remains an important buyer of European arms.

From his exile, Raouf Mellal is trying to raise awareness about what is happening in his home country, at the threshold of Europe. He admits it often feels futile.

“We Algerians feel like we are in a blackout.”

Algeria

After independence from France in 1962, Algerian politics have been dominated by the National Liberation Front (FLN) and the military. FLN was the sole legal party until 1989, when Algeria formally became a democracy. However, the old power apparatus has retained a firm grip on the country.

In 2019, the Hirak protest movement took to the streets to demand democracy. This has been met with ongoing and escalating repression targeting civil society, human rights defenders and journalists.

The regime-aligned national trade union confederation, UGTA, was originally created as a way to mobilize workers against French colonial rule, but is today considered by many to be an instrument of the government, with many union leaders also serving as FLN officials. The UGTA is, however, a member organization of the ITUC.

During the Hirak there were calls for reform coming from inside the UGTA, urging the leadership to “return the UGTA into the hands of the workers”.

In the ITUC’s Global Rights Index, Algeria receives the lowest possible score: “5 – No guarantee of rights.”

Sources: Swedish Institute of International Affairs (UI), ITUC, POMEPS