The Seven Big Losers of the Financial Crisis

The reviving economies of the European Union have seen some positive impact in the labour market over the last year. Developments though are slow and the opinion that wage increases could spur growth is gaining traction.

We need more luxury in our lives! The marketing campaign of the European car industry that centered on an increase in sales of the luxury segment came at a time when growth in the recovering European Union economies has been slow, with some but not enough jobs being created. But the campaign was indicative that economic growth was lopsided. The benefit was largely going to the already wealthy.

Read Swedish version – Krisens sju största förlorare

News agency Reuters recently was given access to an as-of-yet unofficial report on wages in the German labor market. Figures in the report reveal that, in terms of wage levels, the lower 40% of the market have in reality seen their average hourly wages drop between four and seven percent from 1995 to 2015.

The reverse is true for the remaining higher 60% as their wages have increased during the same period of time by one to ten percent. Furthermore, the German government reveal that child poverty in Germany has increased and that 7.5 million Germans today earn less than the national minimum wage of 8.5 euro per hour.

There are signs of a social crisis that Europe is unable to pull free from. The German report is only one of several pointing to this risk. It is in particular the poorer EU countries that have had difficulties recovering from the global financial crisis of 2008.

Many EU countries have experienced halted or discontiuous growth of real wages during recent years, which increases the risk for social tensions. Romania for example had a considerable progress before the financial crisis, seeing real wages increase annually by an average of 11 percent between 2001 and 2008.

The impact of the crisis meant an abrupt halt of growth and wages have been more or less unchanged since then.

The economies of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania paint a similar picture. The annual ten percent increase of real wages before the crisis has been followed by an average of a mere one percent per year.

For the political sphere, these trends serve as warning signs of deepening divisions in society allowing nationalist populism to grow.

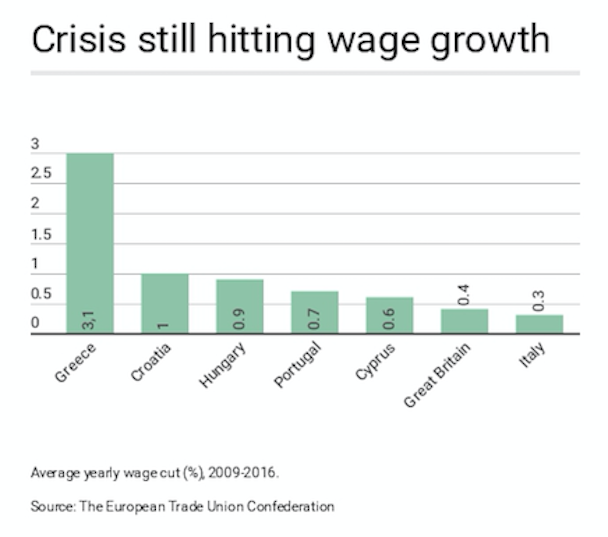

In mid March, the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC) reported that seven EU countries have relatively lower wage levels than before the crisis. Annual real wages (adjusted for inflation) have decreased in Greece, Croatia, Hungary, Great Britain, Portugal, Cyprus and Italy, varying from -0.3% to -3.1%.

“This is very bad news, not only for workers and their families, but also for business” commented ETUC’s Confederal Secretary Ester Lynch.

ETUC is discontent with developments and perceive the low wages as one of the explanations to the slow reviving of the EU economy in comparison to other parts of the world. For 2017 growth in the EU is prognosed at 1.5 percent, which is half of the expected aggregated global figures. From the union perspective, an increase of wages would allow workers to increase consumption, which in turn would lead to increased hiring.

”There has been an overly harsh austerity policy that has created this situation” according to Therese Guovelin, vice president of the Swedish Trade Union Confederation (LO), further explaining that political issues in the EU and the choice to push for an extensive austerity policy had the partial consequence of decreasing the labor share of the economy.

Employer organizations promote another scenario.

” Countries that saw unsustainable rises in unit labour costs before the crisis have suffered more in the years after the crisis”, said Thérèse de Liedekerke, Deputy Director General at BusinessEurope.

Thérèse de Liedekerke, Business Europe.

Many labor market experts encourage an agenda towards stable growth of wage levels. Sweden has among the most stable real wage growth during the full period from 2001 to 2016. Therese Guovelin at LO attributes this absence of the ’yo-yo’-trends of poorer EU economies, to the national policy of expecting unions and employer organisations to take a common responsibility in reaching agreements.

”At the beginning of the 1990’s Sweden had the same high inflation of other countries and while the increase of wages looked good on paper, the full effect wasn’t always to the benefit of employees”.

By the middle of the 90’s Sweden joined other countries in adopting policies that would lower inflation. In conjunction with the 1997 ’Industry Agreement’ between unions and employer organizations that would let the wage agreement for the export industry set the ceiling for all wages. Meaning that all other sectors would thereafter negotiate within that limitation.

The Netherlands and Poland have also had a relatively stable wage growth during the 00’s and 10’s.

Researchers at the European Trade Union Institute (ETUI) have warned that the positive effects on the labor market have come about too slowly and that the large Investment Plan for Europe, the so-called Juncker Plan that the EU commissionary initiated in 2013 to kickstart growth, has been a failure as it hasn’t reached the growth targets that had been set.

Instead they argue that raising wages would be a way to add further stimuli to the EU economies and increase growth.

Translation: Ravi Dar