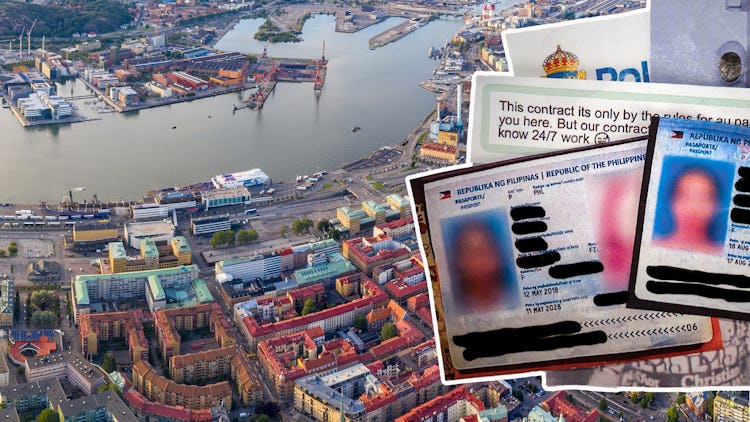

"Ultranationalists are being encouraged by the ruling party"

Ultranationalism – encouraged by the authorities – represents a growing threat to human rights in Burma/Myanmar, says Debbie Stothard, general secretary of the International Federation of Human Rights (FIDH). Discrimination against minorities remains a serious problem.

Debbie Stothard is the founder of ALTSEAN-Burma and general secretary of FIDH. For many years, she has been an important voice advocating human rights and democracy in Burma and the region as a whole. Arbetet Global interviewed her during a visit in Stockholm, ahead of the historic November 8 elections in Burma/Myanmar.

This is a transcript of the interview.

These elections have given rise to hopes of a real democratization of Burma. At the same time, they are taking place against a backdrop of growing ethnical and religious tensions in the country. One of the most vulnerable groups is, of course, the Rohingya. Could you tell us more about their situation?

”This general election will be the first time that the Rohingya has not been allowed to vote. You see, after the Rohingya were stripped of their citizenship in 1982 they were given temporary registration cards, also known as ’white cards’. Now, the white cards didn’t give them the right to travel legally inside the country, but it meant that they could get medical attention in hospitals, they could send their children to school and they could vote in elections. But earlier this year the ultranationalist Buddhist monks were able to pursuade president Thein Sein to cancel the white cards, so that they became of no value whatsoever. That also meant that the Rohingya could not vote.”

Muslims in general have been targeted by the “laws for protection of race and religion”. How has this affected the elections?

“Over a hundred candidates have been disqualified by the national election commission, and most of these disqualifications have targeted Muslims on the grounds that they are ’not really citizens’. We have a member of parliament called Shwe Maung. He is a Rohingya and was elected as a member of parliament in 2010 under the ruling party’s ticket. When his party made laws against the Rohingya and discriminatory laws against muslims this year, he decided to run as an independent. Now he has been rejected on the grounds that his parents were not citizens. So he says, ’hey, excuse me, you let me run in 2010, and I won the seat and there was no challenge to my citizenship status – and now you are challenging me, after I have spent one term as an MP… are you joking?’. But basically, that is what is happening. We estimate that some 3 million voters, and probably even more, will not be allowed to vote. And they are migrant workers, ethnic minorities like the Rohingya, and voters in conflict affected areas.

Now, if we want a durable solution for the peace process, minority groups like the Rohingya need to have legal representation in the parliament. We need to have a political solution, and by disqualifying all these groups, it basically means that the potential for a political solution is getting less and less. “

In this June 26, 2014 photo, a girl, self-identified as Rohingya, stands close to her family’s tent house at Dar Paing camp for refugees, suburbs of Sittwe, Western Rakhine state,. Photo: AP /Gemunu Amarasinghe

Why do you think that these ultranationalist sentiments are increasing in Burma?

”They are encouraged by the ruling party and the authorities, especially by the incumbent president Thein Sein. In 2011 and 2012, before the anti-Muslim riots broke out in Rakhine state and the atrocities took place against the Rohingya, there was a lot of propaganda on social media making people afraid of or hateful against muslims and Rohingya. So when the violence happened it had basically been waiting to happen. Now, what happened was that the media found out that one of the notorious persons on social media spreading anti-Rohingya and anti-Muslim propaganda was the chief of staff of the president’s office. But he did not lose his job… We also had a case when a member of parliament said that people “should hang and kill Rohingya”. He is also notorious for using hate speech against gays – but no problems for him! But when a member of the NLD [opposition party National League of Democracy, editors remark] said in public that ’hatred and extremism is not part of Buddhism’, he was sentenced to two years in jail with hard labor for insulting Buddhism.

We are seeing a situation where the current president, Thein Sein – earlier considered to be a ’one-hit-wonder’ – is likely to get a second term, because he has been able to reinvent himself as the defender of Buddhism in the country. The buddhist extremist movement Ma Bah Tha (’The organization for the protection of race and religion’) has managed to get the four ’national and religious protection laws’ accepted in parliament and then convinced the president to cancel the temporary registration cards. But the main beneficiary of this extremist movement is actually the president.

The Ma Ba Tha is attacking [opposition leader] Aung San Suu Kyi, accusing her of being pro-Muslim, and saying that Burma will become a Muslim country if National League for Democracy wins the election, as well as creating a lot of fear and hatred. We believe that if the military and the president loses the election and are unhappy with the outcome, they could use the Ma Ba Tha to spark riots as a way of denying the election.”

Is Ma Ba Tha to be regarded as a civil movement?

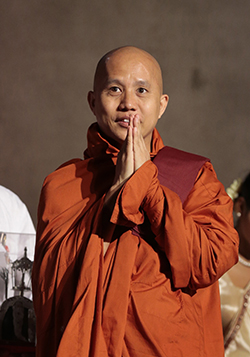

Buddhist monk Ashin Wirathu is the leader of Ma Ba Tha and known for his anti-Muslim stance. Photo: AP /Eranga Jayawardena

”They are not armed, but they are monks that can create so much anger and fear that cilivians can use violence and kill others. That has already happened. Not just in Rakhine state, but in places as Meiktila in Mandaley, and in even in Rangoon.”

You mean that they instigate the violence?

”Yes, they instigate people. They say ’now it is time to defend your religion’, whip up people into a frenzy, put out rumors of that a monk has been murdered by a Muslim, and say that ’we have to take revenge’, and this kind of thing.”

And this is accepted, or even encouraged, by the ruling elite?

”The Ma Ba Tha has been a very convenient way of redirecting the public resentment towards the military. Remember, they have been a military regime for more than 50 years. So you can’t get rid of that resentment that easily. One of the ways is to have Ma Ba Tha put blame on muslims and thereby redirect that resentment. The Ma Ba Tha has been going around saying that ’you should vote for the USDP, the ruling party, because they are doing a good job – forget what they did in the past – and they are the only ones protecting Buddhism’. So we can see that there is a political agenda.

Also, in Burma, in places where there have been clashes and Muslims have been forced to leave, conveniently, the government takes over the empty land. So we are seeing in some parts of the country, that they have been able to expand infrastructure projects. In the city of Sittwe, for example, the Muslim quarters have been emptied and they are probably going to make it into shopping centers or office blocks. In Meiktila, where the Muslim quarter was emptied, they are making a shopping center and a bus terminal. And so on.”

As I understand it, even the NLD has decided not to have Muslim candidates?

”Yes, they were intimidated into that. They had already been accused of being pro-Muslim and funded by Muslims, and they were warned that there would be violence against the NLD if they had any Muslim candidates. At the same time, some of the women NLD candidates are being targeted, because some of them opposed the inter-faith marriage law and the other discriminatory laws that were supposed to ’protect’ Buddhist women from Muslims.”

Let’s return to the Rohingya. How are the government’s plans in Rakhine state affecting them?

”What a lot of people don’t realize is that in some part of the Rakhine state [where many Rohingya live, editors remark], Buddhist and Muslims lived alongside each other. And some of these Buddhists want the Muslims to come back, because they were their customers and business partners. But this is against the view of the authorities, because they try to show that Muslims and Buddhists cannot exist alongside each other. So now they are proposing this Rakhine state action plan, saying that they will reduce poverty through bringing development, on the one hand – but on the other hand, all the Muslims in the state have to reapply for citizenship. And they will get a second class citizenship, not full citizenship.”

That is worrying.

”Yes. And so far that citizenship verification process is going slowly. The success rate is only 7-10 per cent. That is, 7-10 per cent of people who applied to get back their citizenship actually got it. If you don’t get back your citizenship, you will be declared illegal and put in a camp for deportation. Some of them are IDP [Internally Displaced Persons] camps, where displaced Rohingya live with very little access to health care and no education. So we have tens of thousands of school children that have not gone to school since 2012. University students of Rohingya background had their education interrupted and they haven’t been able to go back to university since 2012. We have women and children dying from easily prevented diseases, because they have not been able to get access to medical attention. It is a very dire situation.

That’s why it is not surprising that we had boat people crisis. The Rohingya boat people has been a phenomenon for the last 10 years. What is quite shocking about the current situation is that we see a lot of women and children on the boats. Mostly in the past, it was men who took the boats, because it was so dangerous. Moreover, in this situation, there was a crackdown on human smuggling, so people was stranded at sea. And at first the governments of Thailand and Malaysia pushed back the boats. But civil society responded and in the end Malaysia and Indonesia changed their policy to ’search and rescue’. But we’ve got tens of thousands of Rohingya in Burma, and the sailing season is about to start.”

Migrants sit on their boat as they wait to be rescued by Acehnese fishermen on the sea off East Aceh, Indonesia. Photo: AP Photo/S. Yulinnas

”Part of the push factor is that people that were able to survive in Rakhine state have lost their white cards, which have made them very vulnerable. They realize that they will not have political representation and that, once the election is over, whoever is still outside a camp, is very likely to be rounded up and put in a camp. That feeling of threat has become a push factor.

Now, under the Rakhine development plan, the 7-8 percent of the people that get their citizenship back can’t go back to their homes. They have to live in segregation in communities away from the Buddhists. That is part of the plan, to make a segregated state.”

Basically an Apartheid state?

”That is why bishop Desmond Tutu, when he visited Burma in 2013, actually said: ’This is Apartheid’.

For us, it is very important to address this issue, not as a religious or ethnic issue, but as a human rights issue. Some of these extremist groups hate human rights. It is very strange, because for many years the Burmese public called for human rights and democracy, but now international human rights standards are being seen as ’protection from Muslims’. Groups that used to respect international human rights standards don’t accept them anymore, and that is actually moving some parts of the society closer to the military. And let’s not forget: in the first year of so called parliamentary democracy, the military received a 57 per cent increase in the money that they got from the national budget. And every year since then they have received an increase of about 20 per cent. But they are not using the money for human rights training or peace building… So, the creation of a new enemy justifies the continued power and the resources of the military, both in the political sphere and in terms of its access to resources.”

A Rohingya man, who was displaced following 2012 sectarian violence, carries his daughter at Nga Chaung refugee camp in Pauktaw, western Rakhine state, Myanmar. As the predominantly Buddhist nation of 50 million started transitioning from dictatorship toward democracy in 2011, the rise in radical Buddhist nationalism has taking advantage of the newfound freedoms of expression to fan prejudices against the long-persecuted Rohingya Muslim minority. Hate-filled sermons have helped incite violence that began in 2012, leaving hundreds dead and sending a quarter-million others fleeing their homes. Photo: AP/Gemunu Amarasinghe

READ ALSO: Gáspar Miklós Tamás: ”This is post-fascism”

“Race and Religion Protection Laws”

[caption id="attachment_1806" align="alignnone" width="400"] Ultranationalist Buddhist monk Wirathu speaks during a rally. Photo: AP /Khin Maung Win[/caption]

Ultranationalist Buddhist monk Wirathu speaks during a rally. Photo: AP /Khin Maung Win[/caption]

The four laws known collectively as the "Race and Religion Protection Laws" were adopted this spring by the Parliament in Burma and recently signed by Thein Sein, the country’s President. These are the four laws:

Monogamy Law

Makes it a criminal offense to have more than one spouse or to live with an unmarried partner who is not a spouse.

Religious Conversion Law

A Myanmar citizen who wishes to change his/her religion must obtain approval from a newly established Registration Board for religious conversion, set up in townships. Forced conversion or conversion with the intention of harming a religion is criminilized.

Interfaith Marriage Law

The "Special Marriage Law" regulates the marriages of Buddhist women to non-Buddhist men. A woman under 20 years of age must have parental consent. Local registrars can publicly post marriage applications for 14 days, to see if there are any objections to the proposed unions. If there are no objections, the couple may get married. If there are objections, the issue can be taken to court.

Population Control Law

This law imposes on women in certain regions the requirement to space the birth of their children 36 months apart. Governments of divisions and states get the authority “to request a presidential order limiting reproductive rates if it is determined that population growth, accelerating birth rates, or rising infant or maternal mortality rates are negatively impacting regional development,” or if there is an “imbalance between population and resources, low socio-economic indicators and regional food insufficiency because of internal migration.”

Source: Library of Congress